Decolonising is an important topic for museums and for schools. Recently, teachers from across the Highlands have contacted their local museums seeking support with the process of decolonising the school curriculum. Rosie Barrett, one of our education specialists, talks through our approach to decolonisation on the Museum of the Highlands platform.

A little over a year ago, when I started a consultation process with Highland teachers to inform the development of Museum of the Highlands, teachers were at various stages of their work with themes of anti-racism, Empire and slavery.

Many were following guidance in the report, ‘Promoting and Developing Race Equality and Anti-Racist Education’ published by Education Scotland. This report focuses on ensuring young people can grow up in an inclusive and supportive Scotland. As part of this, there is a clear awareness of the need to interrogate the past.

When I met with staff and volunteers from the fifteen museums that formed Museum of the Highlands, it was clear we wanted to seek, self-consciously, to share underrepresented voices, celebrate diversity and hold ourselves to the highest standards. We knew we couldn’t provide all the answers, but by sharing Highland collections responsibly we could provide stimuli for healthy debate around difficult topics.

The complex interconnections of objects in museum collections with colonialism, and how to approach this in our work, was not something we took lightly – as a project team we spent more time discussing and debating this element of our work than was spent on the other themes together. In this blog, I explain our approach in more detail.

Same objects, different views

A key partner museum in the project for this theme was The Highlanders’ Museum at Fort George. This museum holds the largest military collection outside Edinburgh, including many of the objects represented in the section ‘Colonialism and Conflict‘ on Museum of the Highlands website.

For example, a bugle that once belonged to Drummer John Alcorn of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders. Bugles have been used by the military throughout history for communication and to unite troops. This particular instrument was used to sound the Advance for the Highland Brigade to charge at the Battle of Tel-el-Kebir. During this conflict, British forces intervened in Egyptian affairs in what is now interpreted as an attempt to secure British interest in the Suez Canal.

It was an important object for us to share. A key aspect cited in the report on promoting race equality in schools is the need for “questioning the source of content and the viewpoints represented”. By looking anew at objects like the bugle, we were able to see beyond the traditional narrative; it wasn’t a case of changing the story, but of looking at a more rounded picture.

Our description of the bugle now directly references two viewpoints – “To the regiment, this instrument may be a symbol of military success, but to the Egyptian people it is more likely to signify the loss of independence and the start of 71 years of colonisation.”

As with so many of the stories and objects, we saw this as a starting point to reassess some of these moments from the colonial past. Visitors to the website can explore a range of colonial objects up close too, through the activity ‘Object in Focus’ which shows objects from different angles and invites viewers to speculate about what they might be.

Colonial objects in surprising places

The inclusion on the Museum of the Highlands website of The Highlanders’ Museum opened up this theme for us. However, we also found objects in many less obvious collections – across the Highlands some objects had been collected in the colonies in unclear circumstances, objects that had contributed to Scotland’s involvement in the slave trade, and even toys exploring the Empire within the collection of the Highland Museum of Childhood.

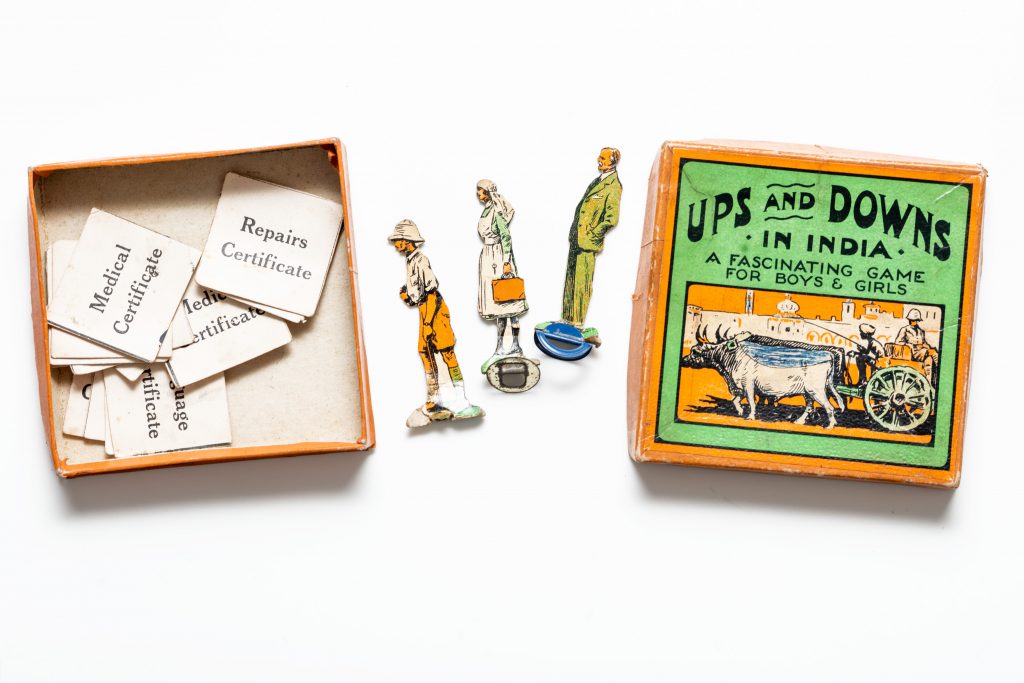

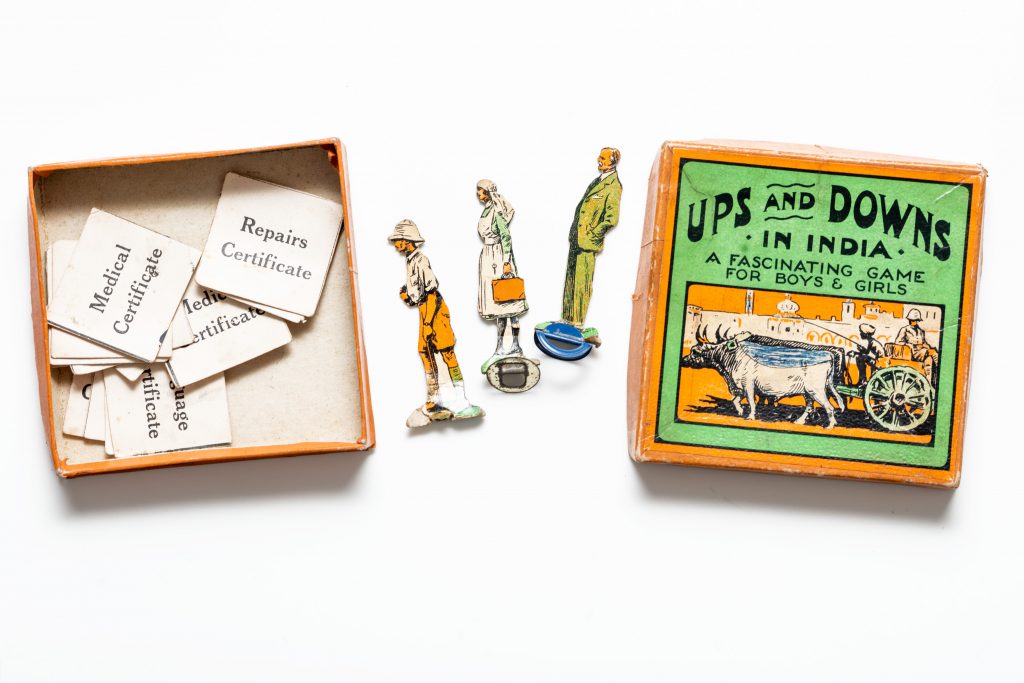

The board game ‘Ups and Downs in India’ is definitely ‘of its time’, and a strong reminder of Britain’s colonial presence in India during the 1930s. It was produced by Homeland Training College in 1930, most likely for the children of people relocating to India for work. Players would move around the board, landing on squares featuring activities such as ‘preaching to the people’ and bible translation, as well as challenges in the form of monsoons and uprisings.

By including objects like this in the project, we wanted to demonstrate the way that colonial history was intertwined with so many aspects of Highland life – in fact, the more we looked, the more it became clear that the theme of colonialism and Empire could be found pretty much everywhere.

The issue of looting.

Many objects currently in British museums are known to have been acquired in circumstances that would not be acceptable today, this includes some objects in Highland collections. Currently, the museum sector is asking questions about how we share these objects, and, in some cases, how we can repatriate them. In our work, we needed to ask an obvious and uncomfortable question – should we include looted objects on the Museum of the Highlands website?

Objects and their descriptions allowed us to be open and upfront about ethical questions around sharing looted objects, and the difficulties we encounter interpreting them. The wording in the object descriptions is chosen to clearly explain the difficulties.

The inclusion of a shield originally belonging to an unknown Abyssinian soldier (from present-day Ethiopia) engages directly with the issue of looting. After the looting of Maqdala by British forces, several objects from the palace made their way to Britain’s shores. Through an interactive story, website users are encouraged to think about the circumstances in which the shield was taken, explore how the news from Maqdala was received in Britain at the time, and question the fate of the object today. High school learners using the website are encouraged to consider a range of issues surrounding this object and form their own opinions.

Slavery and Reflection

The guidance published by Education Scotland is very clear: “To understand the full complexity of decolonising, it is important to remember that racism is rooted in colonialism when Western countries justified the enslavement of people.” Acknowledging the legacies of slavery is an important part of our work on this project. Young people can take part in a range of activities on the website which address colonialism across Highland museum collections.

When developing Museum of the Highlands, we knew there would be lots of stories to celebrate, but also some, such as those involving slavery, that would be heavy with tragedy.

One activity I’m proud of is called ‘On Reflection’ – these PDF activity sheets provide ways for schools to explore different, sometimes difficult, topics. They include discussion questions as well as the opportunity to design or create a memorial as part of the reflection process. Having the time to think and reflect is so important to young people’s development – sometimes we can be in such a rush to learn that we forget that thinking and processing what we have heard can take time, especially with sensitive history.

Several of the ‘On Reflection’ activity sheets explore colonial themes. One celebrates Harlem Renaissance poet Claude Mackay – his Scottish surname is very revealing, shockingly given to his enslaved grandparents by their owner. Another ‘On Reflection’ directly commemorates the victims of the Transatlantic slave trade, supported by an interactive story exploring the Transatlantic crossing, based on the lives of workers on a plantation owned by Highlander James Fowler. Born in Rosemarkie around 1762, James emigrated to Jamaica at the end of the century when the island was a major centre for the production of coffee and sugar. Back in the Highlands, James was presented with a beautifully-engraved snuff box from the East Ross Volunteers – he had been their First Lieutenant after returning from Jamaica.

The story of the snuff-box, now in Groam House Museum, is a painful example of how individual primary sources do not give us a full picture of a person’s life. By sharing the lives of the plantation workers too, we’re able to give more of the story and question how people like James were able to take part in the slave trade.

We hope these activities support young people to form their own opinions about difficult, sensitive and, at times, controversial issues.

Finally, and not for the faint-hearted, we’ve included a ‘Big Question’ debate activity entitled ‘Should Britain apologise for the British Empire?’.

This project was funded by Art Fund and Museums Galleries Scotland and is sponsored by Ilum Studio.